The Old and the Bold

KENT, Ohio — It was autumn 1996. I’m guessing I first met him the same way most people did — at the airport. I didn’t know Dick Schwabe from Adam then, except that he was an airport regular, older than every one of the pilots who mulled around the cramped office, coffee pot, and dispatch counter.

Older than any instructor or transient who found a seat in one of the two short rows of worn black vinyl chairs that faced off from either side of the narrow path leading to the copy machine and bathroom.

The airport is home to the Kent State University flight school, and this modern “office” is not much more than an elongated appendage to the 1930’s maintenance hangar Hugh Robbins built for his Flying Service after the original hangar burned to the ground.

Back then, Dick Schwabe was just a boy with a dream, and Andrew W. Paton Field was the first airport in all of Ohio’s Summit County. The three grass runways were a favorite enroute stop to pilots ferrying World War I JN-4’s — “Jennys” to the U.S. from Canada. Charles Lindbergh, Floyd Bennet and Eddie Rickenbacker all flew from the sod that is now buried under the 4000 ft. strip of asphalt running mostly north to south across the field.

This is the primary runway. Here, student pilots chirp tires on crosswind landings when the wind kicks up from the west. On the gray and drizzly days, airplanes queue in the run-up area as they wait for IFR clearances to depart for an afternoon flight lesson. When you are driving east on Route 59, you can see them there, three-deep, wings rocking in the wind. The engines idle, but inside the cockpit, the pilots’ thoughts are racing toward the day when they’ll fly from the left seat of a jet as an airline’s newest captain.

They don’t see them, but the two other runways, 5-23 and the shorter 9-27 are still there — and are still getting mowed regularly like it was 1920 outside. The school prohibits flight students from using them, so the grass strips have become all but invisible to the young pilots.

The air is peculiar and silent, and then the ground fog suddenly swirls into mare’s tails.

Sometimes, in the morning’s very first light, when all of the sky to the west is still soaked in the blacks and blues of night, you’ll catch a glimpse of the ghost of one of the old Ohio Flying School & Transport Company’s four Jenny’s. It slowly lifts away from the grass to the southwest. The air is peculiar and silent, and then the ground fog suddenly swirls into mare’s tails and reveals the dew-silvered path traced plainly along the length of runway 23’s turf, as straight and true as any beacon.

On the day Schwabe and I met, I had just returned from a training flight and was walking across the flight line for the old door on the east side of the office. The dark windows reflected the gold and salmon sun. The air was cool and I was walking quickly.

As I reached for the doorknob, I looked up to see Schwabe on the other side of the glass in the door. He was wearing a flight cap and a short navy blue windbreaker. As the door swung open, we exchanged brief simultaneous, “good mornings” and smiled a professional greeting common when two strangers acknowledge each other. But as we crossed in opposite directions, I noticed his smile got stuck. I half-turned to watch him walk out to the ramp. He never looked back, just kept walking and smiling.

I was a new face at his airport, but I had a sense that Schwabe had utterly sized me up in the span of our three-second near-collision at the door and he knew something about me.

Weeks later, I was sitting in the chair row waiting for my flight instructor. At the ripe old age of 24, Brett Putnam was easily one of the best pilots I had ever flown with. I felt a little conspicuous. I was 36, and had been flying as a private pilot for 15 years. I didn’t know any of the students here, and they didn’t know me. They rubbed 20-year-old shoulders at the dispatch counter and swapped stories about their weekends while they anticipated fetching the black-zippered pouch with an aircraft ID number painted on it.

The pouch held important documents and the keys to the airplane they would fly today. The dispatcher frequently was a student like them, transformed into a temporary God via the solemn powers bestowed by Part 141 of the Federal Aviation Administration’s regulations and the flight school’s operating handbook. For his shift, the dispatcher has dominion over all of the airplanes in the flying inventory, so he decides if you get the airplane with the cracking interior and door that sticks, or something a little more upscale.

Unlike the rest, I wasn’t enrolled in an aeronautical degree program. I was a walk-in. Here just to try to earn an instrument rating at a good school along side of a herd of young bucks who are, without doubt, now flying you and your family and business associates to destinations all around the world. This school graduates commercial pilots into twin turboprop commuters and jets. But they all start out the same — shoehorned into two-seat blue and white Cessna 152s and four-seat 172s.

I kept my head down and studied an instrument approach plate for the flight I would be making today, while all the regular activity of the place transpired in its odd rhythms around me. The approach “plate” was really just a five-by-eight inch piece of paper that diagrammed exactly how the airplane must be guided to the runway in poor visibility, “blind flying” as it used to be called.

You clip the paper to the yoke (or your leg) in the cockpit, and on approach to landing, religiously attempt to keep the real airplane positioned in the four dimensions described. You do this as the airplane bumps and descends out of a low cloud deck into rain, snow, and gusting wind, and while trying to figure out what the air traffic controller on the radio just directed you to do. Studying the approach in advance was helpful, since I always seemed to get the controller who spoke faster than an auctioneer with a bladder problem and his pants on fire.

Suddenly, the door opened and there was the one guy older than me — Dick Schwabe — and he was wearing the same cap, blue windbreaker and calculating smile. He stood near the door and surveyed the office. A couple student pilots walked by, acknowledged him with at head nod, and kept moving. I was in the chair under the photos of the military jets and there were a few other guys and two young women killing time in the opposite row. Others were navigating themselves toward the dispatch counter.

It was in one of those moments that he did the thing I never would have expected.

Schwabe had a small package under his left arm. I continued to feign an intense interest in the approach plate. I tried not to make eye contact while sneaking quick sideways glances at him to see what he was going to do next. He of course, saw me, and it was in one of those moments that he did the thing I never would have expected, had I lived to be even close to his age.

Before I could quite make out what it was, he had reached into the sack under his arm with his right hand — did a quick underhand wind-up, and from about half the length of the room, pitched some black object directly at my forehead. I was shocked! I ducked, and the projectile whacked the wall behind me and shattered, just missing the frame of the photo.

I looked around to see the other pilots laughing, and then, it got quiet. I was dumbfounded. Schwabe broke the silence, “A pilot needs good eye-hand coordination,” he said, in a hard, scrabbly voice. I had just failed his most fundamental test, so I did what any self-respecting pilot had to do. I reached down between the chairs and found the pieces of the Oreo cookie that had just disintegrated on the wall behind my head. All eyes were on me. I took the largest piece of the cookie, ceremoniously tossed it into the air to catch in my mouth and redeem my pride — and missed.

After that day, it seemed all the pilots talked to me a little more often and over the next dozen years I slowly learned some things about Dick Schwabe.

He was an FAA designated examiner, a pilot’s pilot who flew on check-rides with everyone from primary students, commercial pilots and flight instructors, to the odd duck who might need to get certified in a 1940’s Stearman or J3 Cub. Dick Schwabe literally decided who would be licensed, certified and re-certified. He turned countless young men and women into pilots.

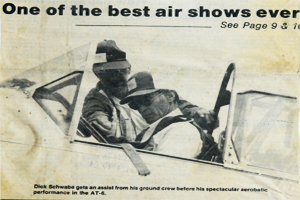

Schwabe’s favorite airplane was the P-47 Thunderbolt, a 2,000 horsepower beast of an airplane that was the largest single engine fighter flying in 1942. He was an aerobatics pilot and air show champion who also liked to fly the smaller 600 horsepower AT-6 Texan. The Texan had a reputation for some wicked stall and spin characteristics. According to one airman, the airplane was ‘‘the best machine ever built to turn gasoline into noise.”

After the war, Schwabe also worked as a physical education teacher, and a high school football and swimming coach. At the end of the 1952 school year, one of his students wrote on a note card to thank him for his help saying, “You are beyond a doubt, one of the finest men I know.” It was signed, “Doc.” Schwabe still has the card.

“Bring me men to match my weather.”

As a young USAAF pilot during WWII, Dick Schwabe flew the “Hump.” Mention this in a room full of 21st century pilots ratchet-jawing about their last flights, and they will soon become quiet. None present will have ever strapped into an unarmed, underpowered C-47 to haul cargo and troops. Nor could they imagine the dangers in the 530-mile long passage over the Himalayan Mountains. No radar, no navaids, and no way to climb much higher than the mountaintops — so Schwabe frequently flew around or between them in some of the worst conditions ever known to flying.

“Bring me men to match my weather,” was a favorite motto of the Hump pilots. Violent thunderstorms, torrential rains, hail, sleet, snow, severe icing and enemy aircraft on this treacherous route claimed 1,300 men and 800 Air Transport Command planes by the end of 1945.

Schwabe flew regular missions over the Himalayas, but never talked about it much. It was another time. To understand it, you had to be there. That’s why, for 60 years, the Hump Pilot’s Association convened an annual reunion. The last one was held in Nashville in October 2005. The association’s operations have since ceased. They finally had run out of enough members. I asked Schwabe once, “What airplane did you fly the most during the war?” He thought for a minute and responded, “all of them.” His logbooks are an encyclopedia of flight. Forty-five thousand hours in the air in every conceivable machine with wings.

So many aircraft, that when I talked to him about it a short while ago, he was starting to lose track. At 86, he was also losing track of some other pieces of his personal past, but his present is very much occupied by his wife, Jean. She looks at the photos of them when they were young and remarks with glassy eyes,

“That part of our lives seems like a dream to me now.” She asks him, “Dick, do you remember when we were dating, and you buzzed the sorority house dance hall?” Dick looks at her and smiles. It was that same smile I saw a decade ago at the airport.

Every pilot knows the day will come when he must return to being bound to the earth. It could be the black vinyl seat in the FBO’s office, or the living room chair near the porch window in a small house full of memories that Jean has lovingly clipped and framed.

Schwabe has come upon that day. He has flown more than I will ever know in a thousand lifetimes. Our flying experiences are forever separated by the uncharitable grasp of time and place, yet we each know that no earthly seat will ever compare to the one attached to a machine that flies.

Seen from above, the artificial boundaries that divide us disappear; flying has an almost supernatural ability to bring together people from all walks of life. For pilots like Schwabe, flying, and airports were not just his life — they are life. Being at the airport reminds a pilot of every flight, and holds the promise of yet one more moment in the air.

This of course, is what draws old pilots to airports and youngsters to the airport fence. They both know the secret. For Schwabe, seeing the young men and women at the university’s flight school struggling, sometimes failing, and succeeding was just as important as flying. Being there, to swap a story, share some insight, make someone laugh, or prompt another to sit up straight, connected us to something more. Even winging cookies at us predisposed something larger than we presently knew or could understand. The traditions and rituals of aviation help forge us into one family.

An airport is a battery that keeps a pilot’s heart beating. It focuses our dreams and our memories. It brings untold perspective and meaning to all and everyone we know — even outside of aviation. I never had an opportunity to fly with Dick Schwabe, but I did learn something important about flying from him.

I know now that his intention never was to discipline my eye or hand to catch a flying Oreo. Rather, it was to teach us all how to live a life, long and well enough — to know when to throw one. And, that smile that got stuck? He gave it to me. A gift of the old and the bold.

Copyright © 2008 Joe Murray, Grass roots. Blue Sky. Stories That Fly.

Rate this story! Click a star below to let us know what you think. 1 is low, 10 is high.

Awesome man!! Hats off to dick shwabe! Am totally impressed with this oldman.

Excellent. Hard to capture the persona of a man that is larger than life. He touched a lot of people in many ways. One may think aviation was his first love, but I think he loved people first. He loved helping others discover their own potential. He made sure we all were true to ourselves and strived to be the best.

I am proud to be “One of his boys”

KSU flight school graduate.

Dave Moll

A great friend. it was a pleasure flying lead plane in formation with you and hearing the pre formation briefings. Thanks for all the shared memories and wisdom as well. I will always be alert for the cookies flying in the air as i maintain my situational awareness!

Sadly Richard has passed today. Rest in piece my friend!

Schwabe was a great man and a great American. I will miss him.

What a wonderful story about Dick Schwabe! I really enjoyed reading it. I earned my instrument rating, CFI, and my CFII with ole’ Schwabe, and sent countless students of mine to him. He will be missed and he will always hold a special place in my heart.

Proud to have known the man, and glad I had the chance to fly with him. Who can forget spending time with him for breakfast on the day of a checkride? Good memories…

A legendary figure, he will be greatly missed. RIP Schwabey.

What a great story! The author completely captures the essence of the man and the airport. I got all my FAA ratings from Schwabe. The knowledge he imparted was invaluable. We were all lucky to know him. He will be missed. Godspeed, Dick.

We will ALL miss you.

Dick Schwabe was truly one of the “Greatest Generation.” Schwabe’s teaching both in and out of the cockpit was invaluable to all of us. In all my travels since graduating from KSU, I have never met another man like him. GODSPEED SCHWABE!!!!

This story brings back a lot of memories. Sad to hear the news today, I enjoyed learning from this great man for all my checkrides.

Dick Schwabe made an incredible impression on me from the tender age of 19. He made you feel like you were not just becoming a pilot, but joining his fraternity. All of us learned so much from him. Godspeed on your flight west dear Schwabe.

I was never fortunate enough to know Schwabie as a flight instructor or pilot. I did get to know him through his work as a Red Cross Water Safety Instructor

Trainer and as a pool director in the summers. He was always teaching, always smiling, and always proud of his students. He once was asked how many lives he had saved as a lifeguard. His response was “thousands, by teaching swimming and safety in, on, and around the water.” I taught water safety with Dick for 15 years.

Joe, great job on this story. I never met Dick Schwable which is clearly my loss. While going through flight training at Purdue I did get to know one or two WW II veterans who were very much like him and had made that Hump flight several times thenselves. I even had the honor to work with one of them in the AV dept. at Purdue. They told many C-47 stories and during those WW II years honed their flight skills on the job, yet they never considered themselves special. We know otherwise.

What can we say? We have lost a dear friend, mentor, and aviation icon in losing Dick Schwabe. True, he never had the fame of Lindbergh or some of the others, but Dick had something more than fame. He had the admiration and respect of every on of us whom he called “one of his boys.” And, yes, I too, swell with pride that he consider me as such…”one of his boys”. Not all aviators get to wear that moniker so it is a prestigious badge of honor.

Richard F. “Right Flight” Schwabe…I learned so much about flying from the man. That knowledge obtained from Schwabie kept me out of trouble while flying. He taught me airmanship: to be in command, to be decisive, to be confident, and above all else, to be safe. In essence, Dick did teach and model “right flight.”

Dick gave me the love of flying and confidence in myself that sparked my career. He insisted that I capture a photo of myself aside a 727 while I was in uniform and send it to him so that it could be displayed on the wall across from dispatch there at the Kent State airport. How could I refuse the man? I would give anything to Schwabe. Schwabe wanted to inspire the kids there at Kent that they, too, could make their dreams come true. He wanted the students to know that they could follow the lead of those who went before them. The “wall” was one of Dick’s ways of teaching outside of the cockpit.

We who knew him loved him dearly. How can I say thank you and pay my last respect to a person like Schwabe, the consummate teacher? I’ll attempt to try: Thank you, Dick Schwabe, for you helped me and hundreds of others to “slip the surly bonds of earth.” You and your legend will live on in future generations of pilots because we who instruct and instructed gave our students a piece of you!

God bless, Dick Schwabe, you will be missed!