Sailcats

A Long Wing to Lift the Spirit

WELLINGTON, Ohio – It’s a sunny early October day with temperatures in the high 70s. Several members of the Fun Country Soaring club at Reader-Botsford Airport in Wellington, Ohio, are preparing sailplanes for flight, doing routine weight-and-balance checks on the aircraft.

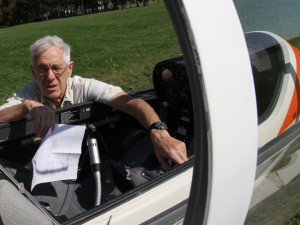

Some, like 73-year-old pilot David Ieuan (pronounced, EYE-yun) Lewis, are seasoned veterans who have spent thousands of hours and miles in the cockpit. Others, like Rebecca Portman, a young mother from Barberton, Ohio have never flown in a sailplane before. On this Saturday afternoon, both will gingerly slip themselves into a slender fuselage sculpted out of composite glass fiber.

To the north, Lake Erie helps to freshen the breeze. The midday sun, so slow to appear while Ohio’s morning overcast lingered, is now fully employed heating the air and generating thermals to lift the gliders up and over the airfield. Each ascending shaft of air is topped with some white-cotton cumulus. Lewis and Portman can clearly see the clouds against the blue sky as each of their glider’s glass canopies are latched–now only a few inches above their heads. The closed canopy mutes the sounds outside. Having only one large landing wheel in the nose of their aircraft, they sit slightly reclined at ground level, and list sideways at about a 25 degree angle. They wait patiently for the tip of that one impossibly long wing–presently resting in the grass–to rise.

Club members gather to soar every Wednesday, Friday and Saturday at this friendly privately-owned airport, 35 miles southwest of Cleveland. Newcomers here are quickly assimilated into the community. All are expected to muck-in and help out with the preparations for flight, and the hobby brings pilots, their families and friends–young and old, from all over Ohio to share their common interest in flying.

Soaring Experience

“At this point in my flying now, the airplane is like an extension of my body,” says Lewis, who has been flying gliders for 57 years. “I don’t have to think through, ‘What am I going to do?’ You just think it and do it.”

Lewis grew up in South Wales and fell in love with aviation at an early age. He learned to fly as a teenager from an air training program run by the Royal Air Force. He came to the United States in 1967, working as an engineer for many years. His aviation accomplishments as a glider pilot encompass a nonstop eight-hour flight in the early ‘70s and a 320-mile cross country flight in 1988.

Lewis also competed in several gliding competitions over the years, where pilots navigate pre-determined courses consisting of turning points, imaginary 1,000-meter vertical rectangles in the air.

“I won some. I lost a lot,” Lewis says. “You’re constantly focused on flying very, very efficiently. If you don’t . . . you’re coming down. It’s not a peaceful thing if you’re flying cross country. You have to make fundamental decisions about every 30 seconds. It’s more of an intellectual exercise, working on where you think the best lift will be.”

The typical glider cockpit contains little more than a stick to steer, rudder pedals to coordinate, brakes and an instrument panel with an altimeter and an airspeed indicator. The lift-to-drag ratio can be altered by the pilot, ranging from 45-to-1 down to about 3-to-1 during a landing.

“Just about every flight you make is different, because the air mass is changing all the time,” Lewis says. “For me, it’s always a challenge to optimize the conditions of the day and conclude with a safe end to the flight. You fly just like the vultures do. You find a lift and you climb in it, get some altitude. Then you ride that out to where you hope the next one is. The bottom line is if you’ve got a strong lift, you fly fast. If you’ve got a weak lift, you fly slow.”

Club president Bruce Grider, who graduated from Kent State University in 1974 with a pilot’s license, shares a respect for the craft similar to Lewis’. “Gliding is a different type of flying,” Grider says. “It teaches you to be a better, safer power pilot. It also teaches you a lot more energy management. You’re improving and honing your navigation and cross-country skills all the time.”

First Time’s a Charm

While glider flights are standard practice for club members like Lewis and Grider, this October day is the very first time for Rebecca Portman, who is accompanied by her husband, David Portman, and 2-year-old son, Zander. David, a former pilot, persuaded his wife to take her first flight in a glider. He and his son will stay grounded today, as the focus this afternoon is on Rebecca.

She will fly in a dual-seat glider with a club instructor at the controls, allowing Portman to fully enjoy the experience. The flight will begin like many others do at Reader-Botsford Airport, with the club’s Piper Pawnee tow plane, a former crop duster, taking off with the glider attached by a tow rope. Once they have ascended together to 3,000 feet above ground, the instructor pilot in the sailplane releases the tow rope and then guides the glider with several twists, turns and spirals over a 25-minute flight, which Portman describes as a “beautiful rollercoaster ride.”

“The first time you’re up and pull the cord,” Grider says “and you have an instructor in the back, it’s still uneasy, because you know you’re cutting loose from the tow plane. That’s your ticket, your power.”

Rebecca’s husband, David, and son Zander watch from a spot near the grass as the tow plane returns for a landing on Reader-Botsford’s 2,750 x 100 ft. turf runway. “Mommy!” Zander shouts in the direction of the Pawnee, thinking his Mom was aboard. “Mommy’s flying,” David explains, pointing to the glider still floating high above.

Confused, the 2-year-old points at the other gliders on the ground, wanting to walk across the field, thinking his mother might be in one of them. After further explanation from his Dad, it finally clicks. “Mommy fly! Mommy fly!” Zander exclaims with a smile, pointing at the sky.

The glider's main wheel touches the grass, and Rebecca's glider rolls to a gentle stop on the runway.

After Portman lands, she excitedly relays her gliding experience to her family. “It was amazing. I loved it,” she says. “Everything was so small from up there. I didn’t want to come down. It was my first time and definitely not my last time.”

An Uncommon Joy

Besides offering glider flights, Fun Country Soaring also provides certified flight instruction that includes a complete soaring curriculum. Of the club’s 43 members, 12 are tow-pilots, capable of aerotowing the gliders into the sky from the cockpit of the single-seat Pawnee. The club has five gliders that the members share, and some pilots are owners.

“We fly until everyone decides they don’t want to fly anymore, or we have to go home,” Grider says. Lewis remarks that glider pilots share a common bond that transcends any personality or ideological differences they may have. He says he’s never seen any “confrontational issues over people’s beliefs in the flying community–ever.”

“I think there’s a mutual respect that you’ve gone through the process of learning how to do this,” the long-time pilot said. “You’ve got a wide variety here. You will find the full range of the political spectrum in the flight community, and, still, just about everyone gets along fine with one another–in this club particularly. I’m looking out for me. I’m looking out for the other guy. That’s the nature of it.”

Despite the commonalities, Lewis believes everyone gets something different out of gliding.

“For me, it was competitive flying,” Lewis says. “For others, it might be instructing. Or, it may be just enjoying the pure joy of flying around and enjoying the fact that, ‘Man, we have a thermal here and I’ve got all this lift for nothing. And I’m using nature to get me up.’ Whatever it takes.”

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.